Nejapa and Chinautla under water stress

By Andina Ayala, Nancy Hernández and Omar Martínez

Borders, cultural behaviors and the hundreds of kilometers that separate Nejapa, in El Salvador, from Santa Cruz Chinautla, in Guatemala, are blurred when talking about water contamination, the lack of institutional intervention and the violation of the health of its inhabitants.

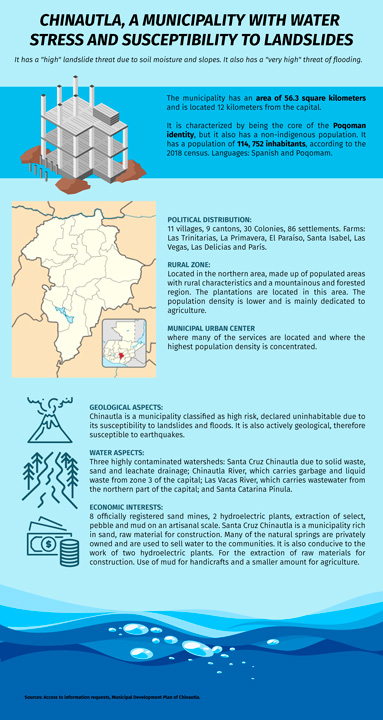

The excessive extraction of the Nejapa aquifer by the industry, construction and sugar cane crops threatens access to the liquid and could cause irreversible damage to the areas classified as maximum protection for water catchment. In the district of Chinautla there are three rivers contaminated by sewage, solid waste and leachate: Chinautla, Saljá and Las Vacas rivers. According to a water availability study by the university Rafael Landívar, the district of Chinautla has been under extreme water stress for years.

The overview in the tributaries is overwhelming, since they run for no less than 30 kilometers, fed by the drains of Guatemala City; when they grow, they carry tons of garbage, also coming from the largest solid waste dump in zone 3 (Guatemalan capital). The contamination is similar in the San Antonio River, in Nejapa, San Salvador, which for 20 years has received sewage discharges from the entire district. Just this year, compliance with article 117 of the Salvadoran Constitution, which mandates the protection of natural resources as a duty of the State, is beginning to be implemented.

Santa Marta Chinautla

On this side of Chinautla, some homes are finding a piece of land and others seem to be in a vacuum. The Santa Marta canton is located 5.6 kilometers southeast of Santa Cruz Chinautla. Here the Las Vacas river flows down, occasionally flooding more than a hundred houses when it rises; it has demolished buildings, including a municipal primary school. Both the Chinautla and Las Vacas rivers are contaminated by sewage from the northern areas of the capital city.

Sulmi de la Cruz’s house, adjacent to a winding main street. She, her sisters and her mother, Luz Altán, feel favored by its location and by having a small well that supplies them with four pilas a day (a pila is a little less than a barrel). “My father taught us that water is not for sale, we share what we can,” Luz said. They draw water following Sulmi’s grandfather’s advice: never draw water in the middle of the day, because the well dries up.

The ammount of pollution is evident and no one has done anything to change the situation.

This canton is closer to the capital’s zone 6, so part of it receives the liquid from the Municipal Water Company of Guatemala (EMPAGUA), the rest of the neighbors depend on the municipal distribution of Chinautla, with both services they have had problems of shortage. Sulmi is a representative of the Community Development Council (COCODE) of Santa Marta, she explains that in her community the percentage of families that have a well is minimal.

“Commonly the water comes every 5, 10 or 15 days. We did a survey to find out how many people have their own well, and out of 200 houses only 10 have one. The problem is that most of these wells are on the banks of the Las Vacas River, so there is some contamination from sewage. A study was done in Linda Vista (another community in the district) where it was shown that the water has feces in it.

Who takes care of the water quality?

Estela López, a resident of the lower part of Santa Marta, who is directly affected by the Las Vacas River, explains that the neighbors of the canton also pollute with garbage and their drains are connected to the tributary. “It is not so easy, some families don’t do it, but others argue: why pay? if the garbage is going to be taken to zone 3 and when it grows it comes back here again”.

The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) seems to know very little about the state of Chinautla’s rivers José Luis Portillo, director of Cuencas, assured that when talking about water quality, they are talking about consumption. “This is basically the responsibility of the district, and it is the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance that analyzes the situation. Portillo is a lawyer, his previous experience was as an advisor to the director of the Authority for the Sustainable Management of the Lake Atitlán Basin and its surroundings (AMSCLAE).

The district of Chinautla, through its Public Information Unit shared a copy of the water quality analysis of the 18 wells in its charge, dated December 2020, according to the results the groundwater shows no contamination. The analyses were performed by the company SOLPUR, S.A. We consulted several experts, among them the biologist Sofía Aguilar, who said that “it is notorious that groundwater is one of the most exposed to contamination by waste infiltration, as Chinautla is a highly populated district it is strange that the wells are not contaminated, we suggest repeating the tests to be certain”.

For the physicochemical results, the biologist recommended another analysis “since the concentration of phosphates, which is a frequent contaminant in water bodies, was not taken into account”. Marco Morales, a hydrology specialist in Guatemala, declined to give an opinion or evaluation on the matter. “The source of the information is important, and the laboratories that can certify results have to have a quality accreditation of the methods used, if I am not mistaken it is an ISO17025 quality certification and the drinking water and wastewater regulations speak of laboratories having to be certified so that the results have a formal-legal validity. This is clearly not the case for this laboratory”.

According to the government’s Secretary of Planning (SEGEPLAN) SOLPUR, S.A. purification solutions, appears as “inactive”. The company appears in social networks as a supplier of chemicals for water purification and not as a laboratory, and is not listed as a certified laboratory on the digital page of the Guatemalan Accreditation Office (OGA).

Other details in the analyses that call the attention are the times in which the samples were taken and the similarity in the percentages, for the head of the Microbiological Reference Laboratory (LAMIR) of the University of San Carlos de Guatemala, Sergio Lickes, this was not as strange as the fact that the samples presented the following parameters of chlorine, water from a well cannot have chlorine, as this element is incorporated in the treatment process.

Lickes found another finding of interest: “the results are compared with the previous version of the COGUANOR standard. The current version is 29005 1st Revision”.

The dilemma of accreditation in Guatemala is that “the controls in the COGUANOR standards and the adherence to the OGA are absolutely voluntary,” said Carlos Fernandez del Cid, master in occupational health and occupational environment. Water quality studies were requested, which by law should be carried out by the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance (MSPAS); their response is that they do not have this information.

Water essential to the right to health

In order to know in what other aspects water contamination may be reflected, MSPAS was asked for a compendium of the 20 most common morbidities in the district, according to Dr. Aida Barrera, 12 of them are related to the scarcity or quality of water.

The expert mentions that to cure scabies, drinking water is needed to wash all bedding and clothing at the same time. “In general, the morbidities that Chinautla presents refer to education, water and environmental sanitation”.

The Las Vacas river infiltrates the wells of the adjoining houses and the Chinautla river, although the women of Chinautla do not use it for consumption, it is common for them to cross it barefoot. MSPAS did not register the illness of Juan Lazaro’s neighbor, a community leader, who saw how one of the workers who manually extract sand from the river contracted “something” that prevented him from earning a living for weeks.

Contamination adds to livelihood problems

Pollution impacts Chinautla in economic decline and undermines cultural practices. One of these is the creation of clay pottery, an inheritance passed down for generations, mostly among women. Julio González, director of Madreselva, an environmental organization that has accompanied and documented the violations in Chinautla, explained that a decade ago it was believed that the pottery was made with contaminated river water.

“The district of the capital increasingly polluted the river basin, with that they killed the economy because the people of the capital understood that the pottery was being worked with dirty water. This was not true. That began with a debacle that added to the environmental crisis: the river was carrying more and more sewage and garbage. The district built a poorly managed landfill that is not a sanitary landfill and the problems for Santa Cruz grew and increased because the landfill itself required sand; more sand began to be extracted from the river”.

MARN explains that Chinautla, due to its strategic location, is being affected. “The proximity of the district of Guatemala. Derived from solid waste management there is contamination, but there is no response from the district of the capital city of Guatemala,” said Portillo the director of watersheds.

The complex reality of Chinautla is seen as a spiral of abuses on a minority people of Poqomam identity. In 2006, the sewage collector in the capital’s Zone 6 collapsed, and according to González, “the district was forced to remove its load and dump more dirty water into the river basin. From 2010 to date, every time there are strong winters or a hydro meteorological phenomenon occurs, Chinautla floods. This is no coincidence.

The opinion of Marco Morales, the water expert, adds more depth to the problem, he says that this is a river that should be intermittent, but it works as an instrument of contamination: “March and February are dry months, but you will see that a cascade of sewage from the drains and leachates from the landfill is falling. That part of the river is carrying sewage, all the untreated water, hazardous and even radioactive waste.”

Violations to the right to life, to their heritage and to their ancestral culture, emanate from the inaction of public institutions. “It is not only the human right to water, but also the right to a healthy environment,” concluded González. The Poqomam population, by reclaiming their indigenous roots have become stronger. This will be discussed in detail in the last installment of this report.

Nejapa: industry and new inhabitants threaten the water table

Luisa Miranda is 27 years old, a single mother; her family is made up of 7 people, who live in the last house in the small village known as El Relámpago in Nejapa. They do not have electricity and it was not until two years ago that they introduced potable water service for which they pay $7.25 every month, even though it only comes twice a month in the summer and twice a week in the winter.

Luisa goes out every day to work in the fields, planting corn and sugar cane, harvesting food and cutting coffee. When she returns home she rests for a few minutes, her feet and hands are the color of the land, and she wipes her neck and arms with a piece of clothing.

Then she takes a pitcher to fetch water from a spring located ten minutes from her house. The path is narrow, between tall trees, wild flowers, birdsong. But Luisa no longer pays attention to these details because it is part of an exhausting routine in search of water. Since she was a little girl, she has been carrying jugs, making 10 to 15 trips a day. The water from the spring is a great help, but it is not drinkable and runs out.

Geological characteristics allow for water catchment

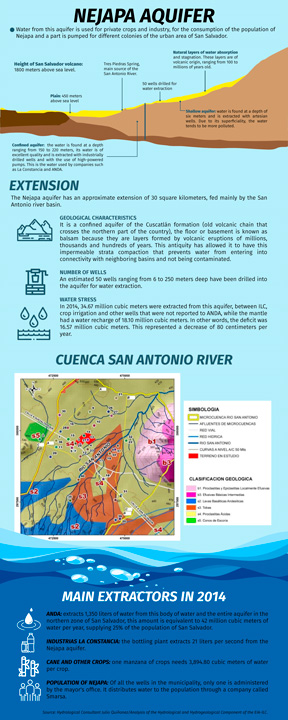

Nejapa harbors eruptive material from the San Salvador volcano and white earth extracts from the Ilopango caldera. The base of the soil is in the Balsamo formation, which is four million years old, and the Cuscatlán is two million years old; these characteristics allow it to have a high degree of impermeability, according to hydrologist Julio Quiñónez Basagoitia.

The water of the aquifer has excellent quality because it infiltrates in the forests of the area of the volcano and does not have contact with other water tributaries, added to its geological formation, make the process of potabilization economic. Also, its depth, at 150 meters, saves resources in the extraction process. This being so, Nejapa is a very valuable aquifer, perhaps the most important in terms of drinking water supply for San Salvador, due to its quality and easy access.

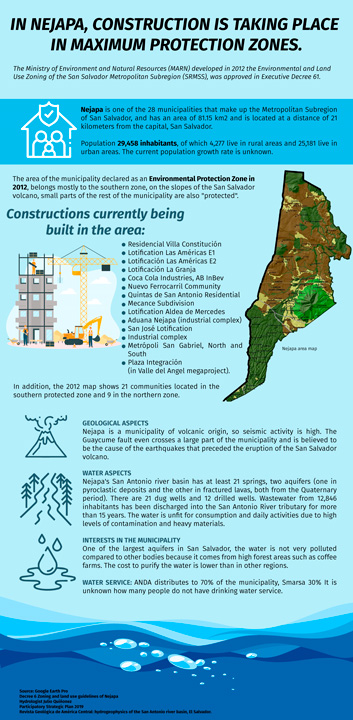

A 2015 report by ANDA (National Administrations of Aqueducts and Sewers) reveals that at that time they extracted 38% of water, with a view to increase by 2%. While private extraction was 53 % and would increase to 60 %. The document records 40 extraction wells in Nejapa, 15 belonged to ANDA and were destined for the metropolitan region, one to the mayor’s office and the remaining 24 belonged to private companies, among them 11 belonged to Industries La Constancia (ILC) company.

An update on the amount of water withdrawn, number of wells and distribution was requested to ANDA’s Office of Access to Information and was denied, the argument: “it may generate an undue advantage to a person to the detriment of a third party”. (From May 21 until one day prior to this publication, an interview was requested to the communications unit of the autonomous company and no response was obtained).

In 2014 Quiñonez, conducted a study on water situation in Nejapa, the water conditions and water extraction from the Nixapa Plant (of La Constancia) and the risk of an expansion. The company intended to increase from 21.4 liters per second to 51.5, that is, 31.1 liters per second more. At that time, the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN), ANDA, the mayor’s office and the specialists’ study, determined that the expansion was environmentally unfeasible because the extraction would cause the aquifer levels to drop drastically. The document revealed that the ILCs, crop irrigation and other wells that were not reported to ANDA, had “an installed exploitation capacity of 34.67 million cubic meters”, while the aquifer had a water recharge of 18.10 million cubic meters per year. In other words, the deficit was 16.57 million cubic meters.

“There was definitely a deficit, at that time it was shown that the district could go into water stress because there was too much extraction. Now, if we compare the level of extraction of all the current projects, we can assure that the aquifer is at its limit and we are already seeing the impacts of water stress, in the lack of water in the communities”.

At that time, ILC extracted 21 liters of water per second, in 24 hours it adds up to 1,838,400 liters, equivalent to 9,192 barrels of water, enough to distribute 2 barrels to 4,596 families and cover the basic needs of three people. The study revealed that if extraction continued at the same rate as in 2014 and the impacts of the climate crisis, such as the increase in temperature and reduction of rainfall, were taken into account, the mantle would cease to exist by 2041.

For Omar Serrano, vice-rector of Social Projection of the university Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA), water is prioritized for industries before the communities because it represents a million-dollar business. “Water is a business, we get five barrels of water per cubic meter and it is worth two dollars. A barrel, bottling it, can fetch up to US$800.”

The UCA and organizations that have been working for 15 years for the approval of a law are not opposed to giving water to industries, they only ask that society be the priority.

Since May 19 at the close of this investigation, an interview was sought with ILC to learn about their social projects in Nejapa, but no response was obtained. On their website they report that since 2016, through the Agua para Nejapa program, the company has benefited 2,020 people in twelve communities with potable water. A minority if one takes into account that with the water they extract in a day, they could benefit more than 4,000 thousand families.

Contamination

Overexploitation of water is not the only problem facing Nejapa. Biological contamination also threatens the water quality of the San Antonio River basin and further aggravates the contamination situation of the Acelhuate, the river that crosses the city of San Salvador carrying industrial waste, sewage and wastewater from entire neighborhoods and communities. It is considered the most polluted tributary of this country.

According to journalist and environmental researcher Nina Lakhani, “90% of the rivers in El Salvador are polluted”. For her, the exploitation of natural resources in Central America directly affects the populations. She assured that in the region conflicts over water are already present and the lack of this resource is visible, especially in El Salvador.

“The lack of water is causing migration all over the world, even in Central America, and we are not far from seeing conflicts over water. The human rights ombudsman said five years ago that in El Salvador human beings will not be able to continue (living) if there is no transformation of water use and (radical) water contamination is avoided.”

Likewise, for hydrologist Quiñones, “climate change scenarios establish that, if we continue like this, by the end of the century El Salvador will be in a very serious water condition, because we will have less rain and temperature increase”. Therefore, it is of vital importance to have a water law that guarantees access to water in quantity and quality to people, but also regulates the amount of water allocated to industry and commerce.

“The water law would establish that those strategic places for the population of El Salvador that have to be taken care of and preserved will not be subject to urban interventions and land changes, and it would not be imposed but based on scientific studies and analysis. We all know that in the country at this time it is easy to pass a (water) law, what we do not know is what kind of law it will be”.

Sanitation of the San Antonio River

It all started in 2000 when three kilometers from its source, in the community of El Junquillo 2, a wastewater treatment plant was built but it was incapable of processing the water of 12,846 people and the industry of the upper zone of Nejapa. After a few months it collapsed due to overload and lack of maintenance, as determined by MARN and the district. The plant is located less than 20 meters from the river.

The biological contamination reaches the surrounding communities, who due to the lack of service seek the river or its branches to wash and carry water for their daily activities. José Raymundo, for 20 years, has prevented the pipes from clogging, without any type of respiratory or other protection, he uses a wooden stick to remove the pestilent water. “There is always a tremendous situation because the bad smell is always going to remain. Sometimes when that water from the factories starts to come down at night, it (the water) goes all the way to the cellars, and the bad smell is worse.”

The Environmental Law establishes that whoever deteriorates essential processes has “the obligation to restore or compensate for the damage”, which would mean that whoever is in charge of the water treatment plant, and the companies that let their gray water go, should respond for the damage caused to the ecosystems of the basin.

Article 7 of El Salvador’s Special Wastewater Regulations establishes that “any natural or legal person, public or private, owner of a work, project or activity responsible for producing or managing wastewater and its discharge into a receiving medium, must install and operate treatment systems so that their wastewater complies with the provisions”.

Official sources have stated that “the current plant generates the following problems: a) gastrointestinal and skin diseases; b) permanent emission of bad odors, c) overflow of untreated water that contaminates the discharge area and neighboring houses (…)”.

The right to water cannot be considered without sanitation. In this sense, the population will wait for the new treatment plant to comply with this part of the law, while this happens, Luisa and other families of Nejapa will continue to carry jugs of water without the certainty that it is drinkable. Industry and housing projects will continue to extract millions of cubic meters of water and commercialize a finite resource.

This report was produced with the support of the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) as part of its “Adelante en América Latina” initiative.